Eva Dell Moore: Difference between revisions

(Created page with "====Biography 1==== From wagenweb,org/lincoln <br> '''The Eva Dell Moore Family''' <br> Submitted by Kathy Meyer <gallery heights=300 mode="packed"> File:1895-wagenweb-001-moore-family.jpg| Francis Marion and Eva Moore, daughter Eva and son Alva about 1895 File:1910-wagenweb-002-moore-family.jpg| Francis Marion and Eva Moore, daughter Eva and son Alva about 1910 </gallery> These two pictures are of my great-grandparents, Francis Marion and Eva Dell (Edwards) Moore, and...") |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 160: | Line 160: | ||

</poem> | </poem> | ||

© Copyright 2008 WAGenWeb | © Copyright 2008 WAGenWeb | ||

{{DEFAULTSORT: Moore, Eva Dell}} | |||

[[category: Pioneer Stories]] | |||

Latest revision as of 14:50, 24 March 2023

Biography 1

From wagenweb,org/lincoln

The Eva Dell Moore Family

Submitted by Kathy Meyer

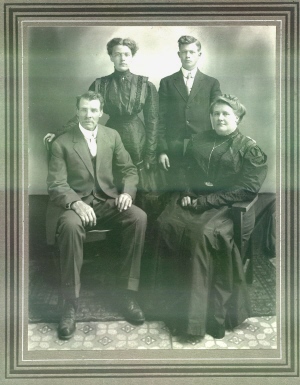

These two pictures are of my great-grandparents, Francis Marion and Eva Dell (Edwards) Moore, and their family. My great-grandfather went by F. Marion Moore, Marion F. Moore, or F. M. Moore, depending on his mood at the moment. His biography is one of those that can be found in the "An Illustrated History of the Big Bend Country" His father, George Washington Moore, is buried in the Spring Creek Cemetery. His mother, Emma (Knapp) Moore died in 1865 and is buried in Eliza Creek Cemetery, Mercer Co., IL. Information about the Moore family and a link to the Knapps can be found at: http://freepages.history.rootsweb.ancestry.com/~mygermanfamilies/Moore.html

Eva Dell (Edwards) Moore was born 13 July 1872 in Osawkie Co, KS. She died 25 June 1942 in Reardan. Her parents were Jane Foltz and Simpson Asbury Edwards. Jane was born in Ohio in 1853. Eva came west in 1882 in a covered wagon with her mother and step-father (Jeptha McLain). Before she died she wrote an account of the trip and the family's first years of farming near Spring Creek. The account is called "Memories of a Pioneer," which is now on the Lincoln County website and can also be found in the Archives at Holland Library at Washington State University. [and follows this account]

The two pictures of the Francis Marion Moore family show F.M., Eva, and their two children, Eva Dell and Alva Francis. I'm guessing that the first was taken in about 1895 and the second in about 1910. Eva Dell was born on 31 Aug 1888 in Reardan and died on 12 Aug 1962 in Spokane. She married Franklin Albert Evers on 5 June 1918 in Reardan. Frank was the son of Louisa Lucht (wife of William Fredrick Lucht) of Reardan. He was born 5 Nov. 1884 in North Dakota and died 4 Dec. 1926 in Davenport. Alva was born 20 June 1892 in Reardan and died in June of 1969 in Spokane. He married Vetrice Laurel Henry, also from the Reardan area. She was born on 20 June 1895 and died in February of 1974 in Spokane.

====================================================

Author Eva Dell Moore Family submitted to the

Lincoln County Washington GenWeb by

Kathryn Meyer, January 24, 2009.

====================================================

USGENWEB NOTICE: In keeping with our policy of providing

free information on the Internet, data may be used by

non-commercial entities, as long as this message

remains on all copied material. These electronic

pages may NOT be reproduced in any format for profit

or for presentation by other persons or organizations.

Persons or organizations desiring to use this material

for purposes other than stated above must obtain the

written consent of the file contributor.

This file was contributed for use in the USGenWeb.

========================================

© Copyright 2008 WAGenWeb

Biography 2

From wagenweb,org/lincoln

Memories of a Pioneer

By Eva Dell Edwards Moore[1] written in 1940.

Submitted by Kathy Meyer.

My first remembrance was being in church, sitting between my mother and a girlfriend in the congregation singing:

Alas, and did my Savior bleed, and did my Savior die,

Would he devote that Sacred head for such a worm as I?

I sat there quietly thinking of the last line and wondering what it meant—I wasn’t a worm, and worms couldn’t talk. I didn’t ask about it at the time, but later I asked my mother if she remembered how old I was when she kept house for Mr. Brown. She said that I was two and one-half years old at the time. The next I remember was being on a train going to Iowa where my mother’s brother, Joe, and family had gone a short time before. We were living near Ozawkie, Kansas, when we left for Iowa, as mother, a widow[2] with one little girl, had made her home with Uncle Joe and his wife when she wasn’t working.

The next event that stands out in my mind was when my mother was married the second time to a man she had known for several years.[3] He was my Uncle Joe’s wife’s brother. I was so glad that I had a father like other little folks had, as I didn’t remember my own father. My new father was a real father to me as long as he lived.

Shortly after this we all went back to Ozawkie where the oldest of my brothers was born.[4] I was about six years old when my father’s father and brother, Tom,[5] decided to go west to Washington Territory where they could homestead some land. They came to our place and stayed all night and left my father’s half-brother,[6] who was 8 years old at the time, with us. They were both widowers, and Tom had no children. I can see them now as they went over the hill with their covered wagons, starting to find a “home in the west.”

Soon after this my folks moved to Howard County, Kansas, where Uncle Joe had gone the year before, as one of his neighbors wanted to rent his farm. Uncle Joe wrote to father and told him to come and run the farm as he, Uncle Joe, was a Civil War veteran and received a pension. He wanted to buy a home of his own, so he went to Chautauqua County, Kansas, and bought a farm, where he lived the rest of his life.

We, after having a crop failure from Chinch Bugs, floods, and cyclones in one day, moved on south where Uncle Joe had settled. I was about 9 years old at this time and had another little brother a few months old.[7] Letters came occasionally from father’s father and brother who had arrived in Washington Territory in the fall of 1878.[8] They had taken homesteads and timber claims, built log houses and other buildings. They told of the climate and everything as they saw it. “A great opportunity for a man to get a start—bunchgrass knee high, and a great future for anyone who gets in in time to get government land.” When they first came, their nearest neighbor was a bachelor about 14 miles away. The nearest Post Office was at Walla Walla, but settlers soon began coming and at the present time the Post Office was about 10 miles away in a farm house. Spokane was only a fur trading post made up of cabins when they arrived. They kept writing trying to get us to come, but it seemed too far and such an undertaking that we never had thought seriously about it. They said that there were no flies in Washington and that seemed good to us because flies, mosquitoes, and other insects were quite plentiful where we lived. They said also that there weren’t any schools in Washington as yet; and I wasn’t impressed much, for I was ten years old and wanted to be a school teacher. I did enjoy going to school.

About this time my mother’s health failed, and she wasn’t able to be up but about half of the time. The doctors said that only a change of climate would help her, but not to make the change too sudden. The folks decided to start west at once. Tom, father’s brother, had written that if we would start, they would send some money to some point on the road where we could pick it up. Also that they would plant a big garden and help us through the first year. After father had sold off all of his property, we had $84 to start on, two gray mares, and an Indian pony that we led behind the wagon. They had written to bring only our bedding, clothing, and camping outfit, so we did. Father had quite a heavy wagon, so he traded it for a lighter one strong enough to stand the trip. He put sideboards on, then built a frame over the wagon bed. He also extended the wagon frame out over the bed so that was as wide as an ordinary bed. We rode out there most of the time, taking turns about riding in the spring seat with father. The boxes of clothing and the camping outfit when not in use were packed in under the bed. We didn’t have a tent but got along nicely as we all slept in the wagon. We had a sheet iron cook stove with an oven in which we baked bread and biscuits—we didn’t have pie or cake very often. We cooked on the campfire when there wasn’t enough room on the stove, as many other people did. Our dishes were tin, making them lighter to carry and not nearly so apt to break. The neighbors all came to see us before we left. Some of them encouraged us, telling us to be sure to write, while others tried very hard to discourage us. It seemed clear out of the world to them then, and for many years afterward, people thought there was nothing but Indians and bunchgrass. The Indians were all on reservations at the time, and we didn’t see any until about two or three years after we came.

The morning we started—it was early in May, 1882, and had been raining for two or three days making things terribly muddy. The mud gathered on the wagon wheels until they were solid disks of mud turning around.

We stayed the last night at Uncle Joe’s, and it was with sad hearts that we ate breakfast and got ready to start. I remember my dear old grandmother,[9] mother’s mother, standing by the wagon. We were all in and ready to start. Uncle Joe and family were there also. Father had carried mother and put her into the wagon, as she wasn’t able to walk. Grandma had her apron over her head, as it was raining, and was crying as if her heart would break, and she wasn’t the only one. We knew we would probably never see each other again in this world, and we never did. All have passed on but two brothers and I.

They watched us until we were out of sight. Father was driving the grays and leading the pony behind the wagon. We also had our dog, Rover, a short-haired, medium-sized black dog that would kill most anything—skunks, rattlesnakes, and badgers—that most other dogs were afraid of, but more about him later. We were starting West and didn’t know what we would find. Indians were on the warpath the summer before, and the name “Indian” caused my hair to stand on end.

When we got back to Howard County, where we had lived, we stopped to see some old neighbors named Hanson. When they found we were starting to Washington, they said if we would wait till they sold their things, they would go with us. We were not in a hurry, as it was early for the main train of immigrants who started from farther east, and we had planned to travel slowly so they would overtake us.

Hanson had a sale, and a week after we arrived there they started with us. The first I remember after we left Howard County was when we arrived in Wichita, out in the edge of civilization at the time. We stopped a little while, and the men went to buy a few groceries, as there weren’t many places they could buy supplies after we got in the Plains country. We were sitting in the wagon when Arville, my father’s young brother, said, “Look at that man eating a corn cob.” Of course, we all looked, and there was a man walking down the street eating a banana. My mother told us what it was, as it was the first one we had seen. When we were ready to start on, “Bounce,” Hansons’ big dog wasn’t with us. We spent some time looking for him and all felt badly, especially the children, to have to go without him. After two months they had a letter from home saying that Bounce had come home.

The next I remember we were at Sidney, Nebraska, on the evening of July 4th. We were camped near the railroad track on the edge of town. There were 13 wagons of us and 32 children and young people, besides the two men, one young and one middle-aged, who rode horseback and hunted wild game for the rest of us for their board. They would start out early in the morning and leave the road or trail and bring game at evening. There were sage hens, prairie chickens, rabbits, and after we were on the Plains, antelopes were plentiful. Often we would see a herd which the men estimated at 500, running over the plains off four or five miles away. They looked like a shadow of a cloud on the ground. We didn’t see any buffalo.

The young men in camp decided to celebrate the fourth, so they made balls of rags, string, and old rope and poured coal over them; and after setting them afire they threw them into the air. When they fell the boys would throw them up again, to the delight of the younger children. Just then the west-bound passenger train came along, blew the whistle and rang the bell to help celebrate, while the passengers waved as if they enjoyed it, too.

We were in the cow country by this time and saw one heard of Texas cattle of 8,000 head being driven to market. Soon after this we came up with a herd of 6,000 head being driven to Ogallalla to be shipped east. We traveled along behind them several days. There were about 20 cowboys and 40 cow ponies so the riders could change ponies, as it was tiresome work for the horses day after day.

The cowboys told us if we would go with them over the cow trails, we could cut off several days to Ogallalla, where we had to cross the Platt River, the first stream of any size we had seen so far. They had two chuck wagons, and my father said he could go anywhere they could. So Hansons and us went with the cowboys, while the others went north over the wagon trail to where a bridge crossed the Platt.

One night there was a terrific electric storm, and if anyone wants to see a real one, go to Kansas or Nebraska. The cattle became restless and showed signs of stampeding, and the cowboys got out and surrounded them and rode around them until after midnight, when the cattle began to lie down. The storm was over, but the cowboys kept riding around them and singing for some time. It didn’t rain where we were but just poured on the part of the wagon train that had gone north. Everything they had was wet, and bedding, trunks, and clothing had to be unpacked and dried.

We arrived at the Platt in the evening and, as the cowboys advised, we camped there while they took the cattle on across. It was a real sight to see those 6,000 head of Texas cattle crossing the river. It was quite wide with shallow banks, and the little town of Ogallalla on the other side. The river bed was quicksand, so they had to keep them moving. Their big horns bobbing as they crossed the stream was something I’ll never forget.

Next morning we started across, as the cowboys had told us they would help if we needed it. Several were on the opposite bank on ponies. We were to keep moving and not stop until we had to. Father took the lead, with Hanson following. About a third of the way over, Hanson’s team stopped and he began calling for father to stop, as the wagon began settling in the mud and sand. Father kept on moving, till near the north bank, his team struck a sandbar and fell down and could not start the wagon. The cowboys rode in and tied the ends of their ropes to each end of the axle. The other end around the saddle horn enabled them to pull us out. Then they took our team and went back and hitched it ahead of Hanson’s; and with the cowboys pulling on the axle, they pulled his wagon out. We had crossed the Platt, which we had been dreading so much as the first large river.

I think my worst disappointment up to that time was that I was a girl and could never be a cowboy. How I did admire them! Every morning they would mount ponies, go to the herd, and lasso the ones they wanted to ride that day. They would change saddles quickly, mount the fresh pony and turn the other loose to run with the herd. After a round of bucking, the new pony was off with the rider after the cattle. The cowboys never left the wagon very far on foot, as they almost lived on their ponies. They advised us to stay near, too, as the cattle would chase anyone on foot.

We camped a few days at Ogallalla to wait for the rest of the train and rested our teams.

We saw our first Indians at Cheyenne, Wyoming. We were camped half a mile from town and saw them at a distance, with their bright colored blankets and headdresses flashing in the sun. They were riding ponies, mostly spotted ones. The women and children especially were very much afraid of them, as they turned and started toward us. They looked hideous, with all colors of paint smeared on their faces. They came close up and sat and talked among themselves awhile, then turned and galloped off toward the town. We were glad to see them go.

While at Cheyenne my mother became seriously ill, and we almost lost her; but she got better, and after a week we started on again. The rest of the emigrants stayed with us, so we were all together when we left Cheyenne.

Somewhere on the plains we met some prairie schooners going east. They told us to look out a little farther on for horse thieves, as they were quite active. We would travel for days without seeing a sign of a settlement. There were prairie dog towns and in some places wild game. Once in a while we would come to a deserted sod house. When we would come to a house with someone living in it, we were always glad and they seemed glad to see anyone.

One night we camped about a half mile from a house where a bachelor lived. We were sitting around the campfire when an owl hooted on one side, and immediately one answered from the other side. The older man who hunted for the camp was also a scout and he said, “That’s no owl. That’s a signal. Every man out.” They got their guns and soon surrounded the horses. Two men were already out guarding them. At night they would turn the horses out to graze and hobble a few of the leaders so they wouldn’t go far from camp. Two men were on guard and would come in at midnight and two more go out, but that night they all stayed out. The next morning we started on; and when we came to the home of the bachelor, we were told he had ten big mules stolen the night before. He was freighting and used the mules with two wagons. We never heard if he got them back or not. We had gone on a day or two when we came to a group of five wagons of immigrants whose horses had been stolen about the same time the mules were. They were away out from nowhere, without horses. We never heard what happened to them.

Another thing I never forgot were the graves along the trail. Sometimes there were four or five together, but more often one lone grave by the side of the road. Some were small and some were large, but most had no name or marker of any kind. One I remember was in a grove of trees with big stones piled all over and a marker, “Helen Hunt, died in 1838.” It was away out there alone.

By this time our funds were getting low as we had failed to get the money Tom was going to send us. We were near Green River, when the rest stopped to do their laundry and to rest their horses. They camped at some hot springs that came out of the side of a little draw, while on the other side was another which had almost ice water. This made an ideal camping place. We went on to Green River, and after we camped father went to town to try to get some work. He got a job cleaning out an old saloon building where there was to be a dance that week. He worked most of the next day and brought home enough food for two or three meals but could find no more work. It was a small town and not much work to be done. That evening the wagon train crossed the river leaving us on that side alone without money or food. We were very much discouraged. Next morning one of the men came down the riverbank and called, “Get on a horse and come over.” He then told father, “If you will give me a lean on your roan horse, I will lend you enough money to get to Soda Springs, Idaho.” There were large hay meadows there, and the Oregon Shortline was building a railroad in that vicinity, so no doubt he could get work there. He came back across the river, and they set up the wagon box on six inch blocks to keep the water out. This was what they all did in crossing streams. So we went on with the rest. The explanation of the roan horse: One of the gray mares had become lame, and father had traded her and the pony for the roan horse. He proved to be a splendid animal and helped break sod on the homestead and do all the things that helps make a home in the west.

We arrived in Soda Springs, Idaho, one evening and father inquired for work. He was told of a widow who had two grown boys who wanted a man and a team in the hay meadow. That night he rode a horse about three miles from town and got the job hauling hay for three weeks. We were out of money again, so father asked the lady if she could advance him the money to pay the loan on the horse as the others wanted to go on. The loan was $13, but she handed him a 20-dollar gold piece. He was surprised and asked, “How do you know I’ll ever pay this back?” She answered, “I think I can tell an honest man when I see one.” He was very thankful, of course, paid off the debt, and we had enough to live on till pay day.

While we were there we had a letter from Tom saying he had sent the money to Salt Lake, thinking we would come the way they had four years before. The trail we came on had been made since they came and was much nearer.

Father worked on the railroad for three weeks, so we were at Soda Springs for six weeks and mother’s health improved. The water was recommended to be very healthful, and she was benefited by it and fully recovered her health.

Tom had written that he was in the Walla Walla country for harvest and as soon as it was finished, he would ride to meet us; so we started on west again. When we reached American Falls, we found the Hansons camped there. They had gone on west with the wagon train but were on their way back to Kansas. They said they had seen all the west they wanted to see. At American Falls we met a family named McDougal, also from Kansas, going to Washington Territory, but no definite or particular place, so they decided to go on with us. The two families traveled on alone from there until we reached our destination. There were the man and wife and six children.

One night we camped on Bear River or Bear Creek in Idaho. It wasn’t a large stream but had timber on each side. Someone told us that the night before some freighters were camped there. In the night they heard a disturbance under the wagon in which they slept. It was bright moonlight and when they looked out, they saw a bear walking off with a side of bacon. Not having a gun they could do nothing but let him go. That night we camped in the same place, and in the night our dog Rover made a terrible commotion. It was cloudy and dark, and we could see nothing but were sure the bear had come back. The dog seemed to be frightened, and father was going to get up and see what was there. But he had no gun, and mother wouldn’t let him get out of the wagon where we slept. Rover thrashed around most of the night, and there seemed to be something wrong. Next morning, as soon as it was light, we found that the dog’s mouth and nose were full of porcupine quills and he was in agony. We could see nothing of the porcupine so decided poor Rover had found something he couldn’t kill. The men tied him down and pulled out all the quills they could find. In about six weeks another quill worked out through the roof of his mouth and nose. For a few days the poor dog could hardly eat.

We had to cross the Bonrock Indian Reservation and, as they had been on the warpath the summer before, we were dreading it, of course. Just before we got to it, we met some people who told us it was safe, as most of the Indian men were out hunting and only a few old men were there. They also told us of a “toll bridge” across a stream where the Indians demanded pay to cross. We were advised not to give them money, as they would let us go across if we gave them a halter rope or most anything. We had very little or no money by this time. When we arrived at the toll bridge, a large Indian came walking slowly, as they do, toward us and asked for “mon,” meaning money, of course. Father told him he had no “mon” but would give him a rope and held up one about six or eight feet long. He took the rope and asked, “Any sug?” meaning sugar. Father said, “Yes,” and took the sugar out of the grub box, dipped out a cupful and held it out to the Indian, not knowing where to put it as he needed the cup. We were all peeking out under the wagon cover and saw the Indian pull out his heavy blue flannel shirt tail, gather the hem up in his hand, and motion father to empty the sugar into the sack he had found. The Indian went off eating the sugar with his dirty hand. We were much impressed and never forgot where the Indian carried his sugar.

We expected to meet Tom any day. When we were out of money again, father borrowed six dollars from Mr. McDougal to buy food. We looked and looked every day, and finally the day came when we saw a man coming on horseback with blankets and camping utensils tied to his saddle. It was he and we were so glad, as we felt our troubles were over. We met him about forty miles west of Baker City, Oregon. The rest of the journey was without much more excitement or trouble. We came through the Grande Ronde Valley, which didn’t seem like a valley to us as it was so hilly. It was getting late in the fall, the horses were tired, and we all were anxious to get to our journey’s end. I don’t remember much of our trip from Walla Walla, only the same day after day.

Our last night we spent at Cheney. As we wanted to make it to Grandpa’s that night, we started early the next morning. It was raining and muddy and slow going, but we arrived at Grandpa’s at 11:00 PM tired and sleepy. They were up and the light in the window looked good to us. McDougals were with us to help eat the good supper that awaited our arrival. They had been expecting us for about two weeks. I do not remember what we had for supper, only the carrots and how awful they tasted to me. None of us had ever eaten them, but we had plenty that we did enjoy. One thing was milk for the children.

Next morning we went to Tom’s homestead about a mile to the south and unloaded and unpacked our belongings. He had a one-room log cabin with a fireplace that we cooked on all winter. Only one man had any money in the whole neighborhood, and he hired some posts and rails split. Father got the job that winter. It seemed to me he worked in the timber most of the time. Tom and he would go on Monday morning and come home Saturday night. Father’s share of the earning was $50, and it took $47 to buy a cook stove and a few cooking utensils. We were certainly proud of that stove. It was a number 8 cast stove with a hearth in front.

In the spring father filed a homestead right on a quarter section five miles west of Tom’s. He and Tom built a log cabin and stable, and we moved to our own home. The cabin had one room 12 x 16 feet. We had no furniture, except the stove, so they made bedsteads of lumber built up high so the trunk and boxes could go under one and a trundle bed under the other making three beds. They made two benches from rough lumber to go on the sides of the homemade table and two about 18 inches long to go on the ends. When we weren’t eating, the benches slid under the table and the small ones were used as chairs.

After coming to Washington, three brothers and one sister were added to the family, making seven children in all. The last three were born after I was married.

When we moved, our house, the cabin, was built on the slope of a hill surrounded by bunchgrass and, once in a while, a large bunch of rye grass. When we drove up and stopped, I jumped off the wagon and almost jumped into a prairie chicken’s nest. It was in a bunch of rye grass in our “front yard” about ten feet from the house. The mother hen flew out from under my feet, and when I looked there was the nest and 14 eggs. We didn’t disturb her, and she hatched the nest of eggs. We watched and before all the little chicks were dry, she left the nest and started off, and they all went with her.

Father broke up about ten acres of prairie that year. He then worked it up with an iron tooth harrow, and it surely took work. He had a team on one harrow, and I drove a team on another harrow following behind him, both walking and going round and round the field until we got it fairly smooth. Then he sowed it by hand in wheat, which he cut for hay and feed. There was some wool grass, and the old pioneers know what that was to work up so a crop could be raised. We made some garden, but Grandpa’s land was older and better, so they planted potatoes and other vegetables there the first year.

McDougals were located on a homestead a day or two after we arrived. Tom helped them get settled, build their house and barn so they could get in before the cold weather came. People helped each other as there was no money to hire, but the exchange of work helped everyone to get along.

The girls didn’t dress in silk and velvet then. If we had a new calico dress, it was kept for our best dress; and if a young man had new overalls, he was as happy as we were in our calico.

The spring after we arrived, there were enough children in the neighborhood to have a school. They decided on a 3-months school, hired a teacher, a 15-year-old girl. She had no certificate but did have a permit. She “boarded around” with the children and had to sleep with one or two as none had an extra room. After a week at each home, she’d start over again until school was out. There was no schoolhouse, so they got permission to hold school in the cabin of a bachelor who was away working somewhere. The teacher had a desk made of rough lumber—also a bench to sit on of the same. We had the same kind of benches with no backs, but they were placed around the wall. When we wrote in our copybooks, we got down on our knees on the floor and put the copybook on the seat. We studied only reading, writing, and arithmetic; and as there were 9 months of vacation, we forgot what we learned before school started again. I gave up hopes of ever being able to teach school as I had thought of since I first started to school when I was 5.

We walked over 2 miles through the bunchgrass most of the way to school until we got a path plain enough to see. Near the path just before we got to school was the grave of a young man who had died the summer before we arrived. At first we had a queer feeling when we passed the grave. Afterward it was decided to have a graveyard there, and one by one the other settlers were laid away there; until now instead of one acre there are four acres in the Spring Creek Cemetery where many of the old pioneers are buried. As I walk through reading the names on the stones, I think of them as I knew them and of the times we went through to settle up and improve and make the country as we have it today. And we had good times, too, and enjoyed being together when we could. As I think of this country now with its beautiful homes compared to what the pioneer had, fine automobiles with trucks, tractors, etc. to farm in the modern way. Many homes have electric lights and are equipped with every convenience. I think what a long way we’ve come. I think of the pioneer who blazed the way to make it what it is, who could not even have the clothing he needed to keep him warm but wrapped gunny sacks around over his shoes and tied them on with small rope to keep his feet from freezing in the winter time. There were times when men went on horseback to Cheney to buy groceries. Often they brought home a 50-lb.-sack of flour and other provisions on their backs so that the family wouldn’t go hungry. People sometimes complain of hard times, but compared to early days they don’t know what hard times are. The pioneer blazed the way for them and gave the best he had in strength and courage to make this a better country to live in. He drove over trails or no trails at all where now we have concrete highways to ride over in comfortable cars. He rode in a lumber wagon or on a Cayuse or Indian pony or walked when he went anywhere.

Thinking of going to Cheney for supplies reminds me of the next fall after we settled on the homestead, when my parents went to Cheney in the wagon to get our winter supply of food and clothing. They left me with my 2 brothers, one six and the other a baby of 2. They were gone 3 days as it took one day to go, one to do the trading, and one to come home. I as 11 at the time with chores to do, two cows to milk, and meals to cook. It was my first time being alone at night, and I couldn’t get very sound asleep, as I felt the responsibility so much. The two nights and three days were a long time to me. How glad I was to hear the rattle of the wagon and see them coming over the hill. No, people don’t know what hardships are! I would not like to go back to those days, but I’m glad I was old enough to have a part in it and grow up with the country. To my knowledge there are only three real pioneers left in this community, but many of their children, including myself, are enjoying the fruits of their labors. In all the hardships and trials that came along, I never heard my parents say they were sorry they made the move or wanted to go back to Kansas. They never seemed discouraged but were always looking forward to something better.

After we were here for a few years, two brothers[10] came from California and bought land not far from our homestead. I married the younger one,[11] who had been a civil engineer on the Southern Pacific Railroad as it was building through Arizona and California. We lived on the farm north of Reardan for 17 years, then rented it and moved to Reardan so our children, a girl and a boy, could have the advantage of good grade and high schools.

=====================================================

Submitted by Kathy Meyer to the WAGENWEB, August 14, 2008.

=====================================================

USGENWEB NOTICE: In keeping with our policy of providing

free information on the Internet, data may be used by

non-commercial entities, as long as this message

remains on all copied material. These electronic

pages may NOT be reproduced in any format for profit

or for presentation by other persons or organizations.

Persons or organizations desiring to use this material

for purposes other than stated above must obtain the

written consent of the file contributor.

This file was contributed for use in the USGenWeb.

==========================================

© Copyright 2008 WAGenWeb

- ↑ Eva Dell (Edwards) Moore was born 13 July 1872 in Osawkie Co, KS. She died 25 June 1942 in Reardan. Her parents were Jane Foltz and Simpson Asbury Edwards. Jane was born in Ohio in 1853. Eva came west in 1882 in a covered wagon with her mother and step-father (Jeptha McLain). Before she died she wrote an account of the trip and the family's first years of farming near Spring Creek. The account is called "Memories of a Pioneer," which is now on the Lincoln County website and can also be found in the Archives at Holland Library at Washington State University.

- ↑ Jennie Foltz Edwards was not actually a widow at this time. She was divorced from Simpson Asbury Edwards. Divorce proceedings were begun and held at Oskaloosa, Kansas, on November 9, 1874. Papers were filed on Nov. 17, 1874, in the Jefferson County Courthouse. Jennie took back her maiden name (Foltz), was awarded custody of their daughter Eva, and was awarded $800 in alimony—which she probably never collected. Edwards failed to appear for the court proceedings, and this history indicates that the two of them struggled financially, which would not have been the case had they received a windfall of $800—a tremendous amount of money in 1874. Jennie apparently did not ever tell her children that she had been divorced from Eva’s father.

- ↑ Jeptha Matthew McLain. Born 1852; married 19 Aug. 1876 to Jennie Foltz in Bedford (Taylor County), Iowa; died 1910 in Reardan (Lincoln County), Washington.

- ↑ Bert McLain, born circa 1878.

- ↑ Tom McLain, born 18 July 1844, died 31 Dec. 1907. Information from his death certificate, on file in Olympia, Washington.

- ↑ Arville McLain, born circa 1870.

- ↑ Mart McLain, born circa 1880/81.

- ↑ They homesteaded north of Reardan (Lincoln County), Washington, which is about 20 miles west of Spokane.

- ↑ Mary Martin Foltz. Born 15 Jan 1820, in Pennsylvania; died 1891 in Peru, KS.

- ↑ Hiram and Marion Moore arrived Washington Territory in 1883.

- ↑ Eva Dell Edwards married Francis Marion Moore on Feb. 2, 1887, at the home of her parents. She was 14-1/2 and he was 37.