White Bluffs Road

This was an article from the Spokesman-Review September 9, 1951, page 51:

By Dr. C. S. Kingston Professor Emeritus of History, Eastern Washington College.

This is the final article in Dr. Kingston's series on Pioneer Roads of This Region. Other articles have featured The Mullan Road, The Colville Military Road, The Old Territorial Road, The Texas Road, The Kentuck Road.

THIS road, so far as pioneer immigration is concerned, is the least important of the early highways. It came into existence because the Oregon Steam Navigation company, that remarkable monopoly of river transportation in the 1860s and 1870s, was eager to push Portland trade and its own freight services into western Montana. The placer gold mines of the upper Missouri and the Clark Fork rivers were drawing thousands of miners and traders to the mountains and they had to be supplied either by way of the Missouri river or from the Pacific coast.

Excerpts from a letter of Simeon G. Reed. president of the O. S. N.,,Co., dated September 4, 1865, to company associates will explain the reasons leading to the decision to expand the field of the company's operations: "Even now the population of that section (Montana) is not less than from 25,000 to 30.000, which is perhaps equal to the population of Idaho at this time. The reports that have been recently received from that section are truly fabulous notwithstanding that they are well authenticated. Within the last two weeks fully 1000 pack animals have left Walla Walla and Lewiston for that country by way of the 'Mullan' road on the Mullan road through the Coeur d'Alene mountains one-stream is crossed and recrossed nearly a hundred times and the road is much obstructed with fallen timber."

Reed went on to say that there was a good wagon road (open country with no obstructions) to the southern end of Lake Pend Oreille and that "from the head of the lake over to Montana is the old Hudson's Bay trail and said to be a good one, and can be made a wagon road at no great expense. The lake is 50 miles long and runs on the direct course, plenty of water, timber for building and wood for fuel, and at the upper end of the lake or at the terminus you are through the Coeur d'Alene mountains, and from that point you are accessible to all the mines in Montana at any season of the year... Perhaps you are not aware that out of 20 steamboats which started up the Missouri river last spring only six of them reached Fort Benton, and then not until July. A few of the balance reached the mouth of Milk river and the others only succeeded in getting as far as Fort Union. I have written at some length in order to state my views clearly, and impress upon you the importance to our company, and the country generally of endeavoring to secure the trade of Montana, which could it be accomplished and my estimates as to resources and population be correct, you will see that our present trade would be doubled, a thing certainly worth striving for."

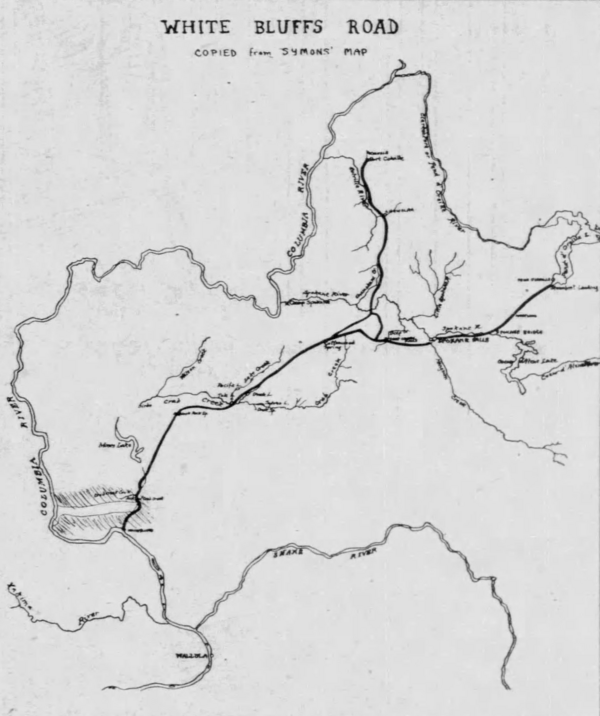

According to the company plans, the Columbia river steamboats would discharge the cargoes intended for the Montana trade at White Bluffs about 50 miles north of Wallula, and from that point carried in wagons across the Big Bend country and the Spokane river to Lake Pend Oreille, and from there on a lake steamer to Cabinet Gorge on the Clark Fork River. At the present time 'Cabinet Gorge, once an obstruction to navigation, is being transformed into a great hydroelectric plant source of power that will turn the wheels of industry. In carrying out its expansion program, the Oregon Steam Navigation company organized a subsidiary known as the Oregon and Montana Transportation company, which built the Mary Moody for use on Lake Pend Oreille and two other steamers, the Cabinet and the Missoula, which were to ply the Clark Fork river above Cabinet Gorge. One was to operate as far as Thompson Falls and the second on the upper river beyond the falls. A stage line was also planned to run between White Bluffs and Pend Oreille lake.

The company went on with its plans to exploit the Pend Oreille route and to capture the Kootenai trade. The mines of this area were yielding satisfactory amounts of placer gold and a famous old trail, the Wild Horse, had many travelers. This trail crossed Pend Oreille river at Sineacateen Laclede and skirted the river and the lake for many miles that could be traveled only with great difficulty during the seasons of high water. A steamer on the lake, could easily carry men and pack trains to a point on the north shore of the lake, thus avoiding to a considerable extent the swamps and sloughs, and then go on to Cabinet Gorge with the rest of its cargo and passengers.

The sale of agricultural products, cattle and horses and all kinds of merchandise to the mining camps had become of large importance to Walla Walla farmers and merchants and the transportation of goods to the mines furnished a lucrative business to the packers and freighters who operated from Walla Walla and Wallula to Kootenai, western Montana, and to many places in Idaho and northern Washington. All these interests opposed the establishment of a shipping point on the Columbia river north of Wallula and the by-passing of the Walla Walla country. For months the Walla Walla Statesman carried articles and news stories denouncing the "White Bluff's Humbug." The country through which the White Bluffs road ran was described as desolate, with no wood. little water and scanty grass.

But there was really no reason for the Walla Walla people to worry over White Bluff competition. It was true that the steamers reaching Fort Benton in 1865 only brought 4441 tons and in 1867, 39 steamers carried 5000 tons. This was the peak year of river transportation to Fort Benton. The building of the Union Pacific railroad (completed in 1869) brought freight more quickly and safely to points in Utah from which it was hauled by ox teams north to Montana's towns and mining camps. Then too, the output of the mines in the Clark Fork country was diminishing and the mining population was moving elsewhere. The steamers, Cabinet and Missoula, were tied to the river bank and later all their machinery was removed, but the Mary Woody remained in service longer and was still operating in 1869.

The main purpose for which the White Bluffs road had been laid out was now gone but it was still the shortest road to the Colville valley and some cargoes for the military force at Fort Colville and for civilian use were landed here to be hauled over the White Bluffs road to Colville, crossing the Spokane river at the La Pray bridge. A storage warehouse stood on the bank of the Columbia and a few stockmen lived along the river but the freighters could not look forward to the riotous pleasures afforded at Walla Walla when they arrived at White Bluffs landing.

The most colorful individual whose name is associated with the White Bluffs road is David Coone (also spelled as Conse and Kunz), who hauled the machinery for the Mary Moody from White Bluffs to Lake Pend Oreille. The engine and boiler were taken from the Col. George Wright, the first steamboat on the upper Columbia. The Indians had great respect for Coone; in their eyes he was a great medicine man, the master of magical powers. On one occasion, just before an eclipse, he told the Indians that he was going to cover the moon with darkness. He had been shot through the palm of one of his hands and then blowing through the bullet hole he declared that he would blow away the darkness that now hung over the world. He concluded his astronomical demonstration by declaring that if any of them stole his cattle, he would blow them right off the earth. While hauling the boiler for the Mary Moody, the Indians looked into the open - door of the boiler and asked him what all the pipe flues were. "Those are guns," said Coone. "This is a big gun, it shoots many times." After that the Indians were very careful when they were near the boiler.

These pranks that Coone played on the Indians sprang naturally from the man's exuberant nature. As a matter of fact he liked the Indians and between him and the Indians the friendliest relation existed. Coone and his wife fed the Indians when they were hungry, advised them, and helped them when help was needed. One old Indian was so grieved by his death that for a long time he refused to eat.

Coone had a 10-mule team and he was accompanied on this trip with the boiler by Mrs. Coone. She tells of how they camped on the bluff west of Hangman creek, where the brick yard road leads down to the valley. There was an old Indian trail here which provided a reasonably good trail down the long hill but getting up on the east side to 4 the level ground (Browne's addition). was a difficult matter. It took Coone and his 10 mules all day to work their way up the gulch now spanned by the tracks of the Northern Pacific railroad. In this connection it may be noted that the probable origin of the name, "White Bluff prairie" for the area between Hangman creek and Deep creek, now crossed by the Sunset highway, came from the fact that the White Bluffs road ran directly across the prairie on its way to Spokane bridge and Lake Pend Oreille.

David Coone at one time had a large ranch near Ringold Bar on the Columbia. He lost so many cattle in hard winters that he gave up cattle business. He raised horses, took freight contracts and readily adapted himself to all frontier opportunities. He was a miner, packer and freighter, a rancher and farmer. In 1900 he was living with his family in Spring Valley, six miles northeast of Rosalia, where he was killed by a frightened horse which reared and fell backwards, the pommel of the saddle crushing the rider's chest.

The comment of one of the old-timers is a fitting obituary: "He was a good man and he died just as he had lived most of his life--in the saddle with his boots on."

Clipping location on The Spokesman-Review page 95