Without a Little Teamwork

[This is family memoir by Margret Clare Wagner Johnson, the youngest daughter of Fred and Lena Wagner. The sketches for each chapter are drawn by Janeth Nash, the author’s granddaughter. Copyright 1972 All rights reserved.]

Spelling and typographical errors have been corrected. Page numbers mark the bottom of the original pages. Photos may be enlarged by clicking on them. The image of a particular page can be accessed by clicking on the Page box on the right had side of the page. All photographs and drawings can be accessed at Without a Little Teamwork Photos. The sequence of page images can be accessed at Without a Little Teamwork Pages]

CHAPTER ONE: The Rich Story

It was an evening in June, supper was over, the dishes washed and put away. Although the big clock on the shelf in the dining room had shortly struck eight, the light outside was still radiant. A few cumulus clouds in the west caught the afterglow of the sun, changing from coral to rosy red to violet. Down by the lake the usual medley of noises, the night hawks beeping, the killdeer plaintive and the blackbirds strident. Co-mingled with the bird calls, the frogs croaked a leisured obligato while in the scab rock above the lake coyotes had started their incessant yelping.

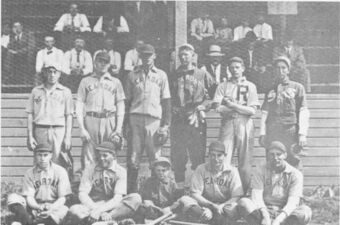

The Collie bitch hearing the opening of the front door, came bounding up to receive an affectionate pat from Papa. Together they made the last final round, closing the chicken house door securely against marauders, checking a mare soon due to drop her foal and closing the granary doors. Then Papa walked up to the road to watch Herman and Gus playing catch. The baseball season had started again.

“How much longer will it take you to finish plowing the half section?” asked Papa as the boys finished their nightly workout.

“Another ten days should do it I should think,” answered Gus. “There’s a lot of moisture in the ground. Good for the wheat.” Page 2

Upstairs in the two front bedrooms the girls were getting ready for bed. Lou the oldest of the Wagner girls was more than ready. Since Mama’s lengthy illness, the responsibility of caring for the house and the younger girls had been largely hers. It had been a long day. How good the bed felt. Bertie, who shared the bed and bedroom with Lou, was standing at the windows watching the boys for a moment as she brushed her long hair. Instead of going directly to bed she went down the hall and slipped into bed with Minna and Rose.

By choice Anne, Minna and Rose shared the big southeast bedroom so the smaller one over the kitchen could be used for a study. I was Anne’s charge. She had been so delighted when Mama unexpectedly produced another baby. I was her joy and delight. When I was too old for a crib, I slept with Anne. Once in my sleep, thrashing about from some frightening nightmare, I had rolled out onto the floor. Thereafter Anne put down pillows by my side of the bed so if it happened again I wouldn’t hurt myself.

At this time Anne, Bert and Rose were in their teens, Minna not quite, while I was seven years younger than Minna.

Anne had already gotten me undressed and into bed. As I lay under the covers my fingers traced the patches of the quilt. Mostly the patches were dull in color, wool and practical, but they were made a bit more gay with bright colored embroidery. They were scraps left over from the yearly stint of clothes making. The blue plaid with red feather stitch was from Rose’s Sunday dress, the brown homespun in cross stitch was Minna’s. Mama taught the girls their embroidery stitches on these quilts at the same time as she made practical use of the leftover bits of fabric.

Lou was the perfectionist and you could always recognize her work for its flawlessness. Anne finally crawled in beside me, drew me into the sheltering circle of her arms. The nightly episode of the “Rich Story” was about to begin.

If you asked any of the girls to define rich, they would say, “Why, you silly, to be rich you have to have lots of money.” That we were rich in love, security, happiness and laughter they all took for granted. Who started the “Rich Story” I have no idea. At the time I was too small to have more than just vague memories about it, but I am sure the story provided entertainment for the girls for months.

The plot of the “Rich Story” was of the simplest. The Wagners had an unlimited amount of money. Each girl in her turn contributed her imaginative bit to the ever recurring theme, as the family moved from one adventure to another they were always surrounded by an endless amount of money.

“Anne, its your turn tonight,” said Rose.

“Yes,” chimed in Minna, “its your turn to tell tonight.”

Bertie anticipating the story added, “Now, Anne, what exactly happened to Donald and Dorothy.”

In the story Lou was married and the mother of twins, Donald and Dorothy. Anne’s great love of children necessitated her need to introduce them into the plot. The twins recurrently were thrown from runaway Carriages, were bedridden with malignant unknown diseases or other catastrophes so Anne could tenderly nurse them back to health.

“Well, let me see.” On and on her voice rose and fell in rhythmical cadence as she developed her plot.

Finally Lou called out, “You kids be quiet in there. Its time for sleep.”

Reluctantly Bert returned to her own bedroom. “Don’t you dare whisper and tell any more after I’ve gone.”

Papa was a past master at telling stories. His sense of timing, showmanship and suspense made even the simplest tale sound exciting. He would sit in the rocker after supper and the eight of us would gather around him eagerly listening.

After Mama died in the summer of 1911, Papa formed the habit of at leaving the ranch sometime in the late fall, traveling to California to see and visit with his brother Charles and then on to San Francisco where he took an apartment until early spring. I was never sure he was leaving until I saw the battered brown suitcase come out from under the bed. It was more than ample for his modest needs, extra long underwear and trousers, a half dozen pair of socks, three or four striped shirts and perhaps a celluloid collar. For safety sake he sewed a money pocket to the inside of his long underwear. He kept an account at the Bank of California, but he carried with him the cash needed for each season.

On the day of his departure his work clothes were neatly arranged in the closet. Papa would go to the bathroom, grab the razor strap, hone his strait edged razor for an extra close shave to last until San Francisco. Normally Papa shaved about once a week unless he had business in Reardan.

For dress up occasions Papa’s suits were always serviceable black serge, usually purchased from Miller, Moore and Flynn department store in Spokane. He favored the Congress slip-on shoes of vici-kid with elastic insets. They felt as comfortable as slippers which was important to Papa Page 4 as he was troubled quite a bit with his feet as he grew older. I don’t remember ever seeing Papa wear a top coat, but he was well padded with long underwear during the winter months.

Last minute talk with Gus about farm business and winter repairs, talk with Lou regarding the household and then the rest of us were lectured on how we should behave while he was gone ending up with, “Be good, mind and help Louise.” If the weather was inclement, Gus would harness Mollie and hitch her to the buggy so Papa could have a ride into Reardan. In fair weather, however, Papa preferred walking in by himself. The train from Hartline to Spokane stopped briefly in Reardan about ten.

“Morning, Fred. Ticket for Spokane? Oh San Francisco. Guess it is time for your yearly trip down there.” The agent and Papa exchanged pleasantries until the steam train whistle reminded them of business at hand. Two hours it took for the train to travel the twenty-five miles from Reardan to Spokane as the line detoured at Deep Creek to offer service to Cheney.

The Northern Pacific bound for Portland left Spokane at eight P.M. Papa always traveled by coach. He denied himself all but barest of essentials in order to give more to his family. The trip south was not too unpleasant as there were always plenty of fellow passengers with whom Papa could visit. After a short lay over in Portland, he caught the south bound train.

For a number of years Papa had a small apartment on Mission Street in San Francisco across the street from the old U.S. Mint. He was happy there with his quarters and his location. Not too far away on Market Street was the Crystal Palace Market where Papa did much of his shopping. He was particularly fussy about his meat. As a little girl I thought living across the street from the Mint was the most glamorous location in the world. Papa toyed for a while with the idea of purchasing the apartment building, but instead he finally settled on more wheat land in Lincoln County.

I’m sure there wasn’t a single motion picture theatre on or near Market Street that Papa did not attend. He loved the movies and went when ever there was a change of pictures. Westerns were his favorite and he enjoyed lots of action. After every performance Papa would come back to his apartment, take down a little black book, jot down the story briefly so he could refresh his memory when he got back home.

What did Papa do to entertain himself during the months he spent in San Francisco? He was always so active physically when he was at home that he probably enjoyed the months of leisured activity. He walked a great deal so that through the years he gained an intimate knowledge of Page 5 many sections of the city. Papa never missed a band concert on Sunday afternoon at Golden Gate Park. He played quite a lot of pool and of course always the movies. There were several retired sea captains from the merchant marine with whom he became intimate. They spent hours telling each other their adventures and then almost daily there was a pinochle game in which Papa would make a fourth.

Papa usually arrived back in Reardan without any advance notice. He would get off the four o’clock train and walk home. Seldom did he get over the brow of the hill without someone spying him and calling out the welcome news, “Papa is home.” How happy we all were to see his beaming face. One time, however, he had shaven off his mustache and I cried when this strange man tried to take me in his arms and call me “Die kleine Christina.”

Each year after Papa went south we learned to wait for and expect two parcels. From Sebastopol came several gallons of strained honey, then shortly thereafter a hundred pound weight of walnuts. The walnuts were kept in Papa’s closet. How great they tasted with big bowls full of apples, or in the batches of candy. I thought they tasted especially good when I filched them from the very large sack in the closet.

It was in the spring, however, when Papa returned that we received the best eating treat of the year. This was a big double crate of navel oranges which Papa checked through as part of his baggage allowance. I was his willing helper as we arranged eight neat piles on the dining room table. “Mudge, Minna, Res-la, Bertie, Annie, Lulu, Hammie and Gus,” I chanted over and over as the piles grew larger and larger until the crate was empty. Papa never ate any himself as he always said, “I get plenty of them in San Francisco.”

Each one took his special pile of fruit to his own secret hiding place. Each decided his own rate of enjoyment, some like me greedy to savor and relish in an incredibly short time, others like Lou spreading out the taste thrill as long as possible. It was only once a year that we had oranges to eat. They were too expensive to buy in Reardan or Spokane. Occasionally for the Fourth of July picnic Lout might buy an orange and a couple of bananas to all to the other fruit in a gelatin fruit salad.

I loved to hear Papa talk about the big Orange Fair in Cloverdale. Every few years Papa and his fried Captain Wieprecht would take the ferry boat to Sausalito where they caught the Northwestern Pacific train for Cloverdale. They could go up in the morning, see the exhibits and catch the evening train back. This trip was made sometime in February when the oranges were ripe.

The first night Papa came home signaled the beginning of our story telling sessions. After supper we all gathered in the dining room. The Page 6 kerosene lamp shed a puddle of soft light on the surface of the table while the corners of the room held dark mysterious shadows. Some sat at the table, some on the corner couch while others relaxed on the floor near the fire. Papa found himself comfortable in his favorite rocking chair. While we all waited with eagerness, Papa scanned his little black book.

Most of the stories Papa told were those he had seen in the movies. If they were not dramatic enough to suit his taste he would embellish the plot as he went along. Many movies were made from Zane Grey’s novels so I am sure we heard these tales. Most of Papa’s stories had very little of sex or love in them. If there was a girl involved in the plot it was in a very minor role. The big thing was action, blood and thunder tales of cowboys and Indians pitting their strength against bandits and outlaws.

Papa always used the German language in telling his stories to us children. I think he always found German a more comfortable language as it offered him greater nuances in tone and color. Sometimes when I was still quite small, I would be so frightened by the events of the story that Anne would have to leave in the most exciting part to put me to bed. Sometimes I fell asleep before the story session was over. Then Papa or Gus would carry me upstairs to bed where I would find myself in the morning and wonder how I ever got there. By the beginning of the First World War the rest of the family had grown beyond the stage of story telling, but I was Papa’s audience for several more years.

Books and stories — books and stories. They were the leavening that raised our busy work-a-day lives into a wonderful shared pleasure. Whenever any sit down kind of group work needed to be done, out would come the latest book we owned. One of us read while all the others kept fingers busy.

When we were growing up the amount of detailed work involved in the preparation of food was prodigious. From late spring until early fall there was an endless procession of food to be processed. First came the red currants to be picked and made into jelly. Then for pies and for sauce we canned gooseberries, strawberries and cherries. At about the same time the first of the garden produce needed to be taken care of. Garden peas, three or four large wash tubs filled at a picking, had to be shelled and canned immediately. After the Fourth of July the Gravenstein apples were ripe. Bushels of apples from our three big trees were peeled and made into sauce. String beans, corn, tomatoes, plums, peaches and pears came on later in the summer and early fall. The shelves in the cellar became more and more crowded with filled half gallon jars ready for the coming winter. It was not unusual to have six to eight hundred quarts of produce stored away.

Because of severe winter conditions, we were not able to raise our own peaches. Usually in September after school started, Lou and Papa Page 7 would make the yearly trek with horse and wagon to Peach, a little hamlet on the Columbia River. They would be gone for two or three days to pick and bring back several hundred pounds of peaches which were then laid out on newspapers in the upstairs study to ripen. Every few days enough would be ready for a canning batch. In the meantime we all had our fill of the fresh fruit. As soon as I got home from school and had changed my clothes, I’d select three or four ripe peaches, peel and slice them into a large bowl. I’d top this with cream so thick it had to be spooned out of the crock. It made a dandy snack before it was time to bring in the cows.

Getting the food ready for the table or for canning was usually done on the front porch with its protective roof. Often a faint breeze came off the lake making this spot the pleasantest place of all to sit and work. Sometimes we gossiped or visited, sometimes we harmonized in song, but if there was a new book in the house, one of us was spared from work y to read aloud for all of us to enjoy.

I guess Mama started the tradition of reading aloud while hand work or was done. The idea of education and culture was never out of her sight. While she spent so many years of her life in poor health and was limited in her physical strength, she always found time and energy to read aloud to us.

There is for me a vague memory, a sort of half shadow tactile one. I am perhaps between three and four years old. Mama is propped up on pillows on the couch in the dining room. I am lying at her feet listening to the musical cadence of her voice which seems to wash over me in gentle happy waves. Would the girls have been embroidering on the patches for the quilts? Perhaps.

Long after Mama was gone I found in Papa’s closet a book of German fairy tales, entitled “Lena Fafer.” The German script I could not read, but I enjoyed the pictures and Lou used to tell me the stories.

Reardan had no kind of a library. The books we read were the books we owned. At Christmas time there was always a book for each of us of one sort or another. The story about a horse “Black Beauty” and about a dog “Beautiful Joe” were two of my treasured gifts. I cried over them both for years. Aunt Barbara and Uncle Joe lived a scant quarter mile from us on the Erdman place. Uncle Joe sold bibles and religious novels. Surely some of his stock that proved to be poor sellers were passed on to us.

Probably Aunt Barbara gave me several of the Elsie Dinsmore books. Elsie was a young girl endowed with modesty and saintly virtue. On one occasion, in one of the stories, Elsie’s father gave her a new velvet a bonnet and velvet muff. She put on the bonnet, admired herself in the mirror Page 8 and stroked the muff enjoying its sumptuous texture on her skin. Suddenly she recoiled from this devilish temptation of pride and thrust the gifts aside. On Sunday as she and her father were leaving for church, he asked her why she was not wearing the new outfit. “Oh, I cannot,” she replied, “I will be thinking about my bonnet instead of God.” I read these books with relish, but I was never tempted to follow in her footsteps.

Another book of mine, religious in content, was “St. Elmo.” Elmo came from a very affluent family. He was pictured as a rake and a sinner in every conceivable term for about three hundred pages. In the nick of time, however, he changed his evil way and became a minister. More than once after reading St. Elmo I considered joining the foreign missions our church was always talking about, but somehow I always managed to change my mind. The thought of leaving home was more than I could bear.

There was one other book that I probably read weekly during the time I was about twelve. It was entitled “A Young Girl’s Wooing.” Many a time Lou would call me, call me and call me to gather the eggs, fill the wood box or do some other chore, but if I were safely hidden in the apple trees or out in the granary, I could ignore her calls and continue the story. The plot involved a dear sweet gentle young maid who out-maneuvered an unscrupulous rival for the love and affection of her brother-in-law’s brother. In all possible situations the heroine excelled in her bid for the young man’s affection. The rival sang Verdi with much aplomb so our gal took secret voice lessons until she could polish off Wagner arias with the greatest of ease. I think the final episode that clinched the romance was when the young girl saved the man from financial ruin when he was caught short on the market by putting up her own securities as collateral. I had no idea at the time what being caught short was all about, but it sounded impressive.

Bertie probably brought home “The Scarlet Letter” and “Little Women” which she must have purchased for some of her English classes. Most of Jean Stanton Porter’s novels were around the house for reading and rereading. When Herman married Martha Knudsen, she brought to their new home a complete set of the novels of Alexander Dumas. That was a real windfall for me to have access to so many books at once. Martha was very generous in allowing me to take them home for reading, one at a time.

CHAPTER TWO: Early Boyhood

We really know very little about Papa’s background. When he finally came to Washington, took out a homestead claim and became a United States citizen, his life, work, attitudes and thoughts were of the present and future, not the past. When I contracted smallpox in July of 1916 and Papa and I were quarantined for a month in a tent up by the spring, he concentrated his time and effort to keeping me happy and alleviating my homesickness. We walked for miles in the warm sunshine checking the ripening grain, sitting above the lake to spy on the house we could not return to and watching the traffic on the county road. To amuse me Papa often sang in his clear baritone voice. When I tired of this he would turn to story telling. I especially enjoyed hearing about his life back in Germany as a boy so he talked quite a little about it.

Papa left Germany sometime in his early teens, sent to a relative or acquaintance in Oshkosh, Wisconsin to learn the baker’s trade. About the time he was eleven Papa became a rebel. He enjoyed the basic mechanics of learning, the math, reading and writing, but rebelled against the militant teachings of his professors.

“What’s so great about the Kaiser?” he asked his Father. “The way the Herr Professor talks you would think he is God himself. Day after day, all we hear is “Deutchland Uber Alles.” Why does Bismarck think the Germans are better than anyone else?”

As he grew older Papa became more and more a non-conformist. Always vocal in his opinions soon he was drawing the attention of the school authorities.

“How can we cope with a son like this,” the Mother and Father asked of each other.

When Charles, the oldest boy was conscripted into the army, Papa said, “They won’t get me. I’ll run away.” Then it was arranged that Papa would be sent to America.

Under Bismarck’s consolidation of the German States into a unified German nation, Saxony occupied a central position. On the Saale River in Saxony Weissenfels, a town of considerable importance during the feudal ages, was situated. On November 3, 1855 Papa was born either here or in a nearby village of Leizling. Papa spoke about the central Square surrounded by homes around its perimeter with fields extending beyond. When the village was first laid out this undoubtedly served as a safety measure. The house and barn were unified under one roof. In rural Europe today it is still common to see this type of one structure building providing shelter for both man and his livestock. As children accustomed to extensive out buildings in ample distance from the house, we thought this was terrible funny. “Imagine living in the same building as the cows.”

Mattilda, his mother, was a peasant, his father, Charles, a petty bourgeoisie. Probably his family were small estate owners. During this period in European history, the vestiges of the old feudal structure still hung on with stubborn persistence against the integrating tide of democratic ideas. There was still a very wide gap between the classes and a rigid scale of snobbery. Against this background, why did Charles step beneath his class and marry a peasant? From the Wagner point of view he committed a cardinal sin. Grandma was a shrewd woman with a driving force that would not be dissipated until she obtained her objective. One of her daughters-in-law, I think it was Adolph’s wife, said, “Grandma was plenty smart. She would have made a good lawyer.”

Grandpa we never knew, but his portrait which at one time graced the parlor wall and later was delegated to the upstairs showed a gentle, sensitive face, full, direct eyes and a kindly mouth. As was common he wore a full beard and mustache neatly trimmed. My guess is that once Grandma made up her mind to have him, he didn’t have a chance.

The house in Leizling or Weissenfels with its small acreage was Page 11 settled on Charles Wagner and here he and Mattilda set up housekeeping. The fact that through her husband, Grandma could assume the right of the landed property, small as it must have been, was something she could never forget. After her husband’s death. when Papa went back to Germany to bring his Mother to Reardan to live with us, Grandma continually belittled her daughter-in-law whose father made a living as a school master.

“Why in the world my son would marry a good for nothing like you, I’ll never know” Grandma expressed in word and action again and again. “What did your Father have that amounted to anything? How much land did he have? Nothing, nothing, nothing.”

Obviously this created a tension in the household that finally became unbearable. Mama was not enough of a fighter to stand up to a strong personality such as Grandma’s, but instead would dissolve into tears. A compromise of sorts was reached when Grandma was moved to the house on the quarter of land just west of the home place. Grandma didn’t want to stay alone nights, so each evening after supper Bertie was sent to spend the night with her. That nightly half mile walk through the fields was often fearful, especially when the yelping coyotes seemed so near.

Grandpa was a gentleman, a product of his environment and upbringing. As such, he could never demean himself by physical work. It was left to Grandma to do the back breaking work in the fields, sowing and reaping the crops, caring for the livestock and looking after the children which she produced in routine regularity. Papa, christened Frederick, was the second child, his brother Charles was two years older.

What was Grandpa’s love was the violin. He must have had a better than average talent playing always with kindred musicians. I doubt that this offered any sort of financial return as Papa always spoke of the land as producing their living. At times there were very meager rations for the children. “I’m sure the stomach trouble I’ve had through the years developed when as a young boy I ate and swallowed food that was too hot so I could have my share,” said Papa each time he periodically went on a hot cooked cereal diet.

As soon as the two older boys were able to hold a violin in their hands they were given lessons by their father. By the time Charles was eleven and Papa was nine, they earned small sums of money playing for the village dances.

Papa made the trip to America by himself, embarking at Hamburg. He neither spoke nor understood any English. While there undoubtedly were many German people also making the crossing with whom he could converse, still it must have been a bewildering experience. Somehow or other he made his way to Oshkosh where he stayed several years learning Page 12 how to become a baker. He was very unhappy in Oshkosh and threatened more than once to leave.

The transcontinental railway was opened in 1869. This opening of the West brought a flood of immigrants from Europe as the railway executives launched a wide scale advertising campaign in the major cities of Europe. Travel offices were available to offer information about the journeys to the settlers and to entice them to the particular part of the West which was serviced by the railway that opened the office. Glowing stories of the unlimited opportunities were carried in most of the largest papers. If the articles were to be believed the West was a veritable “Land of Milk and Honey.” In the barracks where Uncle Charles was stationed the soldiers talked about and sold themselves on the idea of making the crossing to the United States as soon as their tour of service was finished. It wasn’t long after Charles returned to his home that he left and made his way to Oshkosh.

“Fred,” said Charles as soon as he contacted Papa, “how about joining me and going west to California? I understand there is a wonderful opportunity for any young and ambitious fellow out there.” He drew from his pocket a clipping from one of the German papers.

“I’m not quite finished learning my trade here,” replied Papa, “but I’m sick and tired of this grind. I’m willing to walk out on this and join you.”

The two brothers secured enough provisions to last the trip, the other necessary supplies and boarded the Kansas Pacific for the trip across the plains and into California where they disembarked at Sacramento.

Although Papa had been in this country a number of years, he had lived with a German family where the mother tongue was spoken almost exclusively. He did, however, understand some English, surely much more than his brother Charles, fresh from the old country. There had always been a rapport between the two and especially in a strange environment they wanted and needed the support each could give the other. Under these circumstances their choice of finding a job was limited. Finally they heard that field hands were needed near Chico for the harvesting of wheat. Both the brothers were active and industrious. They so impressed their boss that after harvest was over and the other help was laid off, they were asked to stay.

Malaria was still a fairly common disease in the Sacramento Valley during the seventies. The following spring Papa came down with a severe siege of malaria, the only illness in his entire lifetime. The chills and fever persisted until his boss advised Papa to go to a higher altitude until he could get the disease out of his system. In easy stages Papa walked first to Chico and then east out of the valley to the mountains. Where Paradise stands today a burly mining community called Pair-of-dice, so named by Page 13 the gold miners, was situated. Mostly it was jerry built, a conglomeration of shacks and tents. This was Papa’s destination as he hoped to find some of kind of light work to earn his keep until he had fully recuperated. A voluminous woman in an advanced stage of pregnancy was outside a log cabin of on the near side of town. Papa watched her for a few moments as she hung out her clothes. When she noticed him he smiled and began a conversation.

“That is quite a job you have there.” Papa could be most ingratiating when he chose.

“Yes,” she replied as she looked over the stranger who spoke to her.

“You live here?”

“I live in Chico, but I came up here to get out of the heat of the valley.”

“It’s a scorcher down there. I had to leave to try and get over this malaria I picked up down there. Seems to me I feel some better already although I still get some pretty bad spells.”

“This is the best place to get rid of it. I’ve known several people who have come up here for that very reason.”

“I have to find some kind of light work to earn my keep while I’m

here,” continued Papa. “Don’t suppose you know of anyone that needs

a little help for a few weeks?”

“No, I don’t.” The strange lady studied him for a few moments and then volunteered, “I need some help in the kitchen and in the house.” She looked down at her swollen figure wordlessly.

“It may take me a few days to get the hang of what you want done, but I believe I could fill the bill. I’m pretty handy.”

“Know anything about cooking?”

“Just finished learning the baker’s trade back in Oshkosh. I’d have the no trouble on that score. As a matter of fact I’d say my bread is as light and tasty as any you’d find. I’d be most obliged just to work for my board until I can get my strength back. I hate to admit it, but I’m still pretty weak.”

“What did you say your name was?”

“Fred Wagner.”

“I’m Mrs. Larsen. Mrs. Oscar Larsen. My husband has business interests in Chico, but he will be here in a few days. Stay for a day or so and I’ll see how you work out. Then when my husband comes up we’ll see what he says.”

During the weeks that followed, Mrs. Larsen found Papa an avid student. Not only did he take complete charge of the kitchen, but when the baby came there was no one as gentle and efficient in caring for the little one.

Some months later when Papa finally got over his spell of malaria he told the Larsens he thought he should be going back down to find work again and to see how his brother was getting on.

“Fred,” said Mr. Larsen, “I have an interest in a restaurant down in Chico. I’ve just lost my meat cook and I need a replacement. I think you could fill the bill. As a matter of fact I was thinking about offering you the job on my way up here. I’d want you to take charge of the place, run it, do the buying and of course the cooking.”

After some discussion regarding the work, responsibility and wages, the two men came to an agreement. Papa returned to Chico. First of all he wanted to see his brother again, and speak to the farmer who had hired him in the first place to let him know he was not returning to work.

“Well,” said the farmer, “looks like you have yourself quite a job. How old are you anyway, Fred?”

“I’ll be nineteen this coming November.”

There were two waitresses, a dish washer and a cook’s helper. All the help lived on the floor above. The girls shared a bedroom, the two men did the same, while Papa as chief cook and manager had the third one to himself. Early in his employment he learned to barricade his bedroom against the amorous assault of one of the waitresses. Papa had a healthy fear of contracting any social disease. The room and board was part of the salary. Wages were low, hours were long. It was not unusual for Papa to work fourteen to sixteen hours a day. He was frugal with his money and during the time that Papa cooked in Chico he managed to save most of the salary.

This job was one of marking time while he looked around to see something that really appealed to him. What he really wanted was land. Papa was always questioning, asking or reading any matter that pertained to land acquisition. Finally he and Charles heard that land in the Oregon Territory was to be opened up for homestead. They talked it over and looked into the best way to make the trip north.

“Just think, Charlie. Imagine owning a hundred and sixty acres of land. What do you think our folks would say to that?”

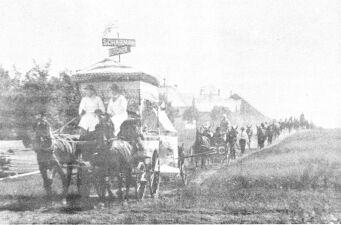

Finally they contacted a group of settlers who were going north to the Willamette Valley. Arrangements were made to join the wagon train.

After they got to Portland they could find others for the trip east. They shopped carefully for the right wagon, horses and other necessary supplies.

We know few details of that trip. In the Grants Pass area there Was rumor of Indian unrest so watch was posted each night. Also during the day riders scouted ahead of the main party for any Indian sign, all the men of the group taking their turns. It must have been taken in a leisurely manner as there was a lot of livestock that could not be moved too quickly. Papa’s skill in bread making earned him the job of camp baker.

The Oregon Steam Navigation Company, which held the monopoly of river traffic on the Columbia, wanted the Bg Bend area developed to increase their downstream traffic of goods. George Atkinson, a Congregational missionary, was one of the first men to analyze the soils and experiment with the possibility of growing wheat in the area he called the Inland Empire. His praise of the area as a wheat growing Eden was a boon to O S N’s own plan to increase river revenues. They hung their advertising programs on this peg. “Wheat, wheat wheat. The best wheat Country in the world to be found only in the Big Bend of the Columbia.”

The advertising posters along the water front in Portland appealed to the Wagner brothers. They decided to §0 up river and have a look for themselves. Papa and Charlie must have used one of the O S N river barges for their trip from Portland up river going as far as The Dalles or Umatilla. From there they would have traveled the old Oregon Trail to Walla Walla.

They first settled near Waverly about thirty miles southeast of Spokane on Latah Creek. They found work temporarily with an established a settler there by the name of Kingbaum. Mr. Kingbaum especially liked Papa and tried to interest him in one of his daughters. While Papa was not sold on the daughter, he did like the region and would probably have taken up a homestead in this area, but here the Indians intervened. A band of Nez Perce Indians up from Steptoe Butte raided the area burning homes, grain and driving off livestock. In caves along the creek Papa and Charles protected the Kingbaum livestock and their own horses and supplies while the family banded with other settlers. When things simmered down the Wagner brothers decided they would try their luck elsewhere, where they might find the Indians more peaceful.

CHAPTER THREE: This Is My Land

The early archives of Lincoln County are kept in the basement of the Court House in Davenport. I asked the county clerk if I could see the original certificate that made Papa a proud land owner of one hundred and sixty acres of rolling prairie. It took some time before she finally found the dusty tome, its pages yellowed with age.

On page eighty-two in the yearbook for 1888 we find the following — “There has been deposited in the General Land Office of the United States a certificate of the register of the land office of Spokane Falls, Washington territory, to secure Homesteads to actual settlers on the public domain.

The claim of Fred Wagner has been established and duly consumated in conformity of the law, May 26, 1888.

Grover Cleveland, President of the United States.”

Thus, officially did Papa take legal claim of the southeast quarter of section four, township twenty-five, north of range thirty-nine.

In 1862 Congress passed the Homestead Law. In its provision, a citizen of the United States could acquire one hundred and sixty acres of public Page 18 domain provided he lived on the land for five years, made his home on it, cultivated the ground and paid a fee of about sixteen dollars. Between 1862 and 1900, 80 million acres were released to Homesteaders.

While Papa and Uncle Charlie were not citizens of the United States when they filed for a homestead, they had taken out first papers. The government decreed this was an article of good faith and as such they were permitted to secure a claim provided their final papers had been taken out before the five years were over.

About a year and a half before Papa became legal owner of the home place, on November 16, 1886 at Spokane Falls, Territory of Washington, he appeared before the Judicial District Court. Two witnesses, Moon Getty and James Leslie testified that Fred Wagner had fully complied with the laws relative thereto, namely that he had resided in Washington Territory for one year, and in the United States for at least five, and he behaved as a man of good moral character. Swearing before Judge George Turner his allegiance to the United States of America, Papa was admitted to citizenship.

When Papa and Uncle Charlie decided to leave the Waverly district and seek an area where the Indians were more peaceful, they traveled by horseback northeast to Spokane Falls. Here they stayed for several weeks exploring the country round about. There were two requirements they especially wished to fulfill when they finally decided on a parcel of land. One was that the claim had easy access to water, the other that it be as near a railway loading point as possible.

The Northern Pacific Railway had been authorized in 1864 with the government extending generous grants of land to the company. Every other section of land along the right of way was deeded to the railway. Construction began in 1864, but it was not until seventeen years later on June 25, 1881 that the Northern Pacific rails were finally laid into Spokane Falls.

The following year a town called Fairweather was plotted by Hooker and Still of Cheney. This was along the proposed right of way for a branch railway from Cheney in a westerly direction, servicing the land of the Big Bend area and then making connections with the main line to the coast at Hartline. In 1889, Fairweather was renamed after C. F. Reardan, engineer of construction of the line.

It was in this area, twenty-five miles by wagon road from Spokane which followed old Indian trails across the White Bluff Prairie that Papa and Uncle Charlie decided to settle. The year was 1883.

A mile north of Reardan the prairie is level land, then it gently dips into a small hollow. On the east side of the hollow is an outcropping of rim rock. At the base, a small lake. Today it is pretty much silted up, Page 19 but when Papa arrived the lake was clear, eight to ten feet deep, and several acres in size. The boundary line of the quarter section Papa selected to homestead ran through the center of the lake. Above it to the north a swelling hill of sage and scab rock. At the back end of the quarter were several springs that ran pure clear water summer and winter. In the draws that contoured the base of the hills the timothy and other grasses were tall and luxuriant.

“Yes,” said Papa in talking it over with Uncle Charlie, “This place will suit me very well.”

Uncle Charlie selected a quarter of land a mile further north. This also had natural springs. The big requirement of a water supply had been satisfied. Pleased with their choice, they returned to Spokane Falls and filed their claim.

Early summer was already warming the hills when Papa returned to Reardan, His wagon was piled high with tools and household supplies. In slow, reluctant plodding, the cows followed behind, tethered by thongs to the rear axle to keep them from straying. A span of four horses pulled their load through dusty ruts onward to the west.

The governor of Washington Territory had this to say about the pioneers, “Nearly all the newcomers were of a superior class of settlers for few would undertake to remove themselves to a part of the country as distant as this. Without ample means of vicissitudes of at least two seasons, it would be impossible to survive.”

Well, there was money saved through the years for just this under taking, there was a willing mind, a sturdy body.

Looking over the lay of the land Papa decided the hill above the lake was the most advantageous for safety and security to build his sod dugout shelter. With pick and shovel he dug deep into the earth, saving the upturned sod as support and insulation for the logs that formed the roof. The alder trees that were clustered against the hill by the lakeside were felled to provide timbers for the roof.

When the hay and grasses ripened, Papa took his scythe to cut them and raked them into piles until they were dried. Then again the hay was mounded up into stacks to provide feed for his animals in the long winter months. His own provisions were easy to obtain. Prairie chickens and rabbits were more than plentiful, a single shot would provide a meal or two. Flour and salt were easily stored staples for bread to add to his diet of meat. For a change of pace occasionally Papa would ride to the canyon four miles north for a mess of trout which were abundant in Spring Creek.

Capps Place, a scant mile away, was the stage stop on the old Fort Spokane route. It also served as post office for the area until 1889 when Page 20 the post office was moved to Reardan. Papa could ride over in a few minutes to visit with the Capps and any interesting wayfarer. Papa and Charlie helped each other often when work needed more than one hand for accomplishment.

But however busy he was, however weary, Papa would take a few moments here and there to listen to the song birds, to watch the setting sun or to admire the bloom of a wild flower.

As the home place was near the old Indian trail, the Indians continued to camp by the lakeside when they were in transit from one area to another. This practice Papa never attempted to stop. As long as he had charge of the ranch any Indian was welcome to spend the night on the place, with ample food provided for the horses, and milk and eggs for the Indian and his family.

Papa was rather proud of my piano playing ability and often he would call me in to play some of his favorite tunes for some bypassing Indian. I can still remember some stoical, silent Indian, complete with long braided black hair, atop of which sat a stiff black hat, sitting in the parlor until my piano piece was finished and then Papa ceremoniously escorting the same Indian out the door. What the various Indian braves thought of my accomplishment was never vocalized. Perhaps they considered this as accepted ritual before the giving of gifts of food. As I remember, no Indian wife was ever invited into the house to hear me make music. This was an honor only accorded to the men.

It always amazed me to see the skill with which Papa was able to communicate with the Indians. He was not much of a linguist, but his pantomime was excellent and with the necessary descriptive actions to suit the words, his mixture of German, English and Chinook somehow always got across.

One story of Papa’s that was one of my favorites, I heard many, many times when I was a little girl. Papa was still living in the sod house above the lake. A cold southern wind had brought with it a dismal wet rain. As Papa came in from work he looked out across the lake where he saw the thin smoke of a camp fire. Nearby was a wagon without cover, but from that distance he could not make out exactly how many were in the party. He went into his house, stoked up the fire, cooked and ate his evening meal. Then, as was his custom when anyone was camped at the foot of the hill, he went down to talk with his over-night guests. Secure in the warmth of his heavy mackintosh, he strode down to the camp.

The Indian, huddled in a blanket with his back to the wind, was warming himself over the glowing coals. In the bed of the wagon the squaw was on her knees, leaning over and crooning to her babies.

“How,” said Papa with a smile of welcome on his face.

“How,” answered the brave, at the same time scanning Papa’s features.

Desultory conversation about the weather, the feed for the horses, times and conditions followed. Finally, the Indian spoke about his two sons who he said “Were heap big sick.”

Then for the first time Papa turned his attention to the occupants of the wagon. He looked at the little fellows huddled in the wagon bed under deer skins, felt their foreheads and immediately ascertained the seriousness of their condition.

“Hot, hot, too hot,” said Papa demonstrating with his hands on his own forehead. “Sick, much sick. We take boys up hill to house. I see if I can get fever to come down. Yes?”

“Yes.”

Papa took the larger of the two boys and cradled him in his arms as he strode away toward the house. The squaw picked up the other lad and wordlessly followed. The Indian stayed behind just long enough to see that the horses were hobbled, the fire banked and then he also made the climb upward.

The one room shelter was filled to overflowing as all entered. In a moment the lantern was lit to cast an eerie glow over the room and its occupants. Papa placed the two little fellows in his bed, covering them with all the bedding he had available. Some form of infection, probably scarlet fever, had sent their temperatures soaring. Hour after hour Papa applied cold compresses. He made a mixture of kerosene and sugar which he fed to the boys in small amounts from time to time. Hour after hour through the night, through the next day and on into the second night, Papa nursed the boys with all the skill and tenderness at his command. Finally the fever broke, the boys fell into a natural sleep, and Papa turned to the father.

“It’s all right now. Boy get well, boy get well.”

Was Papa cognizant of the prevailing Indian philosophy as practiced by the Eastern Washington Indian tribes? Indians were in the habit of killing any medicine man who misused his powers as far as illness was concerned. A medicine man was first of all a sorcerer. If magic failed, the capacity to cure the sick vanished. To the primitive mind, only success in recovery of patients made for a healer. If a patient died, so according to tribal law, should the medicine man.

From the Indian point of view, Papa had taken on to himself the responsibility of a medicine man. With this act, all that followed was his doing. Knowing Papa, I’m sure even this would not have stopped him from offering help where it was needed.

Fortunately the fever broke, and after a restful sleep, the boys were well enough to travel.

When Papa first took over the homestead, he occasionally lost a horse or a cow, as it was then still open range country and only a brand identified the owner of the stock. Some must have been rustled by passing Indians, others just strayed too far afield. After word was passed along the Spokane River about his medicinal powers, the Indians came more and more to trust him and respect him. From then on Papa would send word along the line that a brindle cow, or a piebald pony was missing, and the Indians would keep an eye out for the stock and return it to him if they found it.

One day several months later, as Papa came in from work, he found on his doorstep, a pair of soft deerskin embroidered and beaded moccasins. A grateful mother was returning her thanks.

The seasons passed one to the other in rapid succession. Gradually, more sod was turned under and the ground was readied for planting. Although there was scant rainfall each year, about ten to fourteen inches, the accumulated humus from decaying grasses turned back into the ground, made for an excellent growing medium for wheat. The first wheat was flailed by hand onto a blanket, the same primitive method that is still in use in underdeveloped areas of the world. When we watched the Filipino peasants flailing the ripened rice stocks, tossing the plastic blankets on which it was piled into the air to let the wind catch the chaff, I thought, “Why this is exactly how Papa did it so many years ago.”

In a year or so, work was started on the railway. This brought many construction workers, which in turn developed a need for goods and services.

Conrad Scharman, a German, was on the lookout for a place to start a meat market and thought our part of the country offered possibilities. The development of the Inland Empire was still in flux, Spokane, Cheney, even our town was bending every effort to become the hub. Scharman liked the Reardan area, thought it offered him good business possibilities. He was scouting around for a source for his meat supply.

“There are a couple of bachelors north of town,” he was told, “Why don’t you see what they have to offer.”

With this as a lead, Scharman mounted his saddle horse and started north. He stopped first to talk to Papa. There was an almost instant rapport between the two men, a feeling of mutual respect and trust. It marked the beginning of a friendship that lasted a lifetime.

“How many steer do you need?” asked Papa.

“I can’t rightly say just now. Guess I’ll have to play it by ear.”

“You have a place to slaughter yet?”

“No, not yet, but I’ll make some arrangements. Just now I’m trying to line up my supply.”

“Well,” continued Papa, “I’ll be glad to take care of the slaughtering for you if you like. I’ll need some kind of a holding pen, but there is plenty of grass and water here. Come winter I’ve made arrangements to go down the canyon and split some rails so I can put up a corral.”

Details were gradually worked out to the satisfaction of them both. It was a good source of money that Papa needed to build a house and to buy equipment. The extra work that this entailed meant nothing to Papa. He was young, he was strong and he was ambitious. His farm was going be built solid and permanent.

Papa took roots in this prairie country. A happiness and a pride deep within him more than compensated for the toil and back-breaking labor. “This is my land” was the song in his heart, and finally, on May 18, 1888, this became a fact recognized by law.

CHAPTER FOUR: The Farmer Takes a Wife

It was a Sunday morning in late fall. There was a crisp, sparkling and invigorating feeling to the air. The frost of the night had etched the cobwebs on the grasses into delicate patterns. The smoke from the chimney arose straight into the sky, not a breath of wind was near to challenge its upward flight.

Papa was shaving and trimming his mustache. While he worked, his mind was busy inventorying his summer accomplishments. The first and biggest job done was the new house, built this time, not on the hill, but close by the county road. The money that Mr. Scharman had paid him had made it possible to buy the lumber. On several of his trips into Spokane Falls, Papa had brought back rough sawn pine, a foot in width and four inch battens. With a saw, claw hammer, chisel and a keg of square topped nails, along with the lumber, Papa plunged into the task of building himself a real house. That this was a new venture, about which he knew little, daunted him not in the least. To an outsider, the house may have looked jerry-built, but to Papa it seemed a palace. How much more spacious it was than the dugout shelter on the hill! How big the kitchen seemed, the bedroom downstairs and the full loft overhead for storage!

In addition to building the house, Papa had broken ten more acres of sod. The wheat, now all harvested, had yielded a sizeable crop. The hay was all stacked in a crude shelter for feed for his animals through the coming winter. Yes, all in all, it had been a good year.

Still there was a nagging ache he could not define. What was this restlessness that made him so pernickety? “I know what is bothering me,” he said to the mirror on the wall, “I need a wife and children to give this place a completeness. Now, where am I going to find a wife?”

Unmarried women were almost non-existent around the Reardan area. Goodness knows, there were few enough women of any kind, let alone some marriageable ones. Papa mulled the problem over in his mind for several days. Finally he thought, “I’ll go see the Erdmans. Barbara may be able to come up with a good idea.”

Papa went down to see Uncle Charlie. He was rather vague. “Charles, could you keep an eye on my stock and the place for a few days? I haven’t seen the Erdmans since we left Waverly. Thought I’d ride down that way and see how they are getting along.”

Louis Erdman had been one of the first friends Papa had made when he came into the Washington area. Erdman had come west from Wisconsin, had herded sheep for a time and then taken out a homestead. He had met and married Barbara Gabelein, who also came out to Washington Territory with a family by the name of Swartz.

The last few miles, Papa kept urging his mare to hurry. He thoroughly enjoyed the companionship and good conversation of these two dear friends. At supper, relaxing at the table, Papa turned to Barbara with a smile, “Barbara, I’m not getting any younger. I do feel that I’m in a position now to support a wife and family, but I don’t know where I’m going to find a wife. I’d like someone just like you, if I can find her. I don’t suppose you happen to have an unmarried sister back in Ger many?”

Barbara laughed, “Why, Fred, thank you for the nice compliment. It does happen that I do have a sister back home. It is my sister Lena, who is three years younger than I.”

“Really? Tell me all about her.”

“Well, she is my only sister and sort of-my baby. I pretty much had to look after her when Mama died and Papa remarried. I’ll tell you what I can do. I’ll write to Lena, tell her about you and invite her to come out to Washington. I think I have a photograph somewhere.”

Barbara picked up the family album that lay on the table, turning the leaves. “There,” she said, “that’s Lena. Do you think she looks like me?”

Papa studied the picture carefully. “I like her face. It’s so much like you in many ways. I think I’m half in love with her already. Lena, eh? Lena, it’s a pretty name.”

Finally, Barbara got up from the table to clear and wash the dishes. The two men continued to sit around the table enjoying their beer. There was much talk — about Papa’s new house, Louis’ new acquisition of land, about the crops and weather. In a day or so, Papa returned home, pleased with the progress he had made and content to await further developments.

In the meantime, Barbara wrote to her sister in great detail about Papa; what he was like, what he had and how much she and Louis liked him. “Come on out and meet him, Lena. I think you would be happy with this man,” she concluded.

When Mama received Barbara’s letter, she read it and reread it. Lena Gabelein was twenty-four years old. She hated to admit it, even to herself, but many in Bayreuth considered her an old maid. Did she have the courage to make that long trip all by herself? Would she find a good marriage at the end of her journey? Lena dearly loved her father and was loathe to leave him, but her step-mother, who had married her father when Lena was five, still managed to frustrate and embitter her. There was much soul-searching before Lena finally made up her mind to come to Washington Territory.

Weeks passed as Mama packed and readied for the trip. First of all were the hope chest things put in the bottom of the melon-topped trunks. There were the hand-loomed linen cloths, towels, sheets and pillow cases. Each piece carried in red the letters L. G. and were numbered, apparently as they were finished. One, thirty-seven, eighty-five as each came off her loom. Then, the beautifully embroidered pillow shams, the goose down pillows and the bedding, all part of her dowry.

All the clothes Mama owned and all she could afford in new ones, were packed next. She never did get over her love of pretty clothes. How she must have loved the one that was made to wear at her wedding. The photographs, taken the day Mama and Papa were married, gives one an idea of what it was like. A brown two-piece heavy silk with the bodice outlined with a pleated yoke of some heavier material, perhaps satin, was neatly fitted and gold buttoned. The sleeves also had a band of the same material finished with a trim of two-inch wide woven lace. The same lace was fashioned into a collar to frame her pretty face. The skirt was floor length, voluminous, falling in soft pleats. Over it, as added embellishment, was an extra short half-skirt draped to one side. Her hat, a sailor, with its high crown covered with hand-made flowers, would also have been lovingly packed in her commodious luggage.

At last, Mama started on the long, frightening trip across the ocean.

Her uncle Charles Gabelein and his four children came to meet the ship to welcome her. Uncle Charles had a very flourishing carpet business in New York City. His home reflected in comfort and charm, his rising affluence in the business world.

Several weeks were spent in New York City, resting, sight-seeing and getting to know the younger cousins. Finally came the day for traveling on. Her Uncle Charles and family said good-bye to a reluctant, frightened woman as they saw Mama off on the train. After what seemed an eternity, the train stopped at Spokane Falls. Barbara was there to meet her.

What visiting, what chattering followed, as the two sisters were again united. Lena must see everything in Barbara’s house, must get to know Louis, who was so kind and good. Lena, in her turn, must tell all about the family, her trip and her New York experience.

At last, word was sent to Papa, who came to the Erdman place as soon as he could make arrangements to leave his own. Papa galloped up to the house, sprang from the saddle, eagerly ran up and knocked on the door. A comely young woman answered his knock.

“You’re Lena, aren’t you?” She nodded affirmative. “Well, I’m Fred Wagner. Come along with me while I water the mare and bed her down. We might as well start getting acquainted.”

Side by side they walked down to the watering trough. While the horse was drinking his fill, they took time to look at each other. “I trust him” thought Lena, while “She’s just what I want” was Fred’s inward conviction. It was as easy as that.

Soon, plans were made for the wedding. Papa would go back home and return to Spokane Falls with a wagon so they could bring on, not only Mama’s things, but supplies they would shop for together. The Erdmans would bring Lena, traveling by light spring wagon in which they could stow all of Lena’s baggage.

On June 27, 1887, Lena Gabelein and Friederich K. Wagner were married in the German Lutheran Church of Spokane Falls. Mama was so pleased to find such a church. This was a service familiar to her, the vows were spoken in her native tongue. It was a good omen. Louis and Barbara Erdman were the only witnesses to the ceremony.

After the service, they probably went to the California House on Howard and Trent Street for their wedding dinner. There would have been wine and beer on this festive occasion. Mama said Papa was a little tipsy from the wine. Looking at the wedding picture, one can imagine that Papa felt rather care-free at the moment in spite of his new responsibilities.

There was a tearful good-bye from Mama and an auf Wiedersehen by Papa, as the Erdmans left to return home. The honeymoon was over all too soon. As they went shopping for supplies the next day, Papa bought a western side saddle as his wedding gift to his new bride. It was a luxury he felt he could hardly afford, and yet, he wanted Mama with him when he rode after the cattle and other livestock.

It was, in many ways, a difficult adjustment for Mama. There were so many days of loneliness and isolation, such a strange contrast to the urban community she had always known. The Indians coming by the house frightened and startled her as they moved so quietly and appeared, so it seemed, out of nowhere. The coyotes howling through the night set her nerves on edge, but the utter stillness seemed even worse to cope with.

She found her strength and security in Papa. Only when she was with him did she feel safe. He was intuitive of her need and in many unexpected ways, supplied her the courage she did not have herself. For instance, Mama was afraid when she made the last nightly trip out to the outhouse by herself, the long shadows of dusk were eerie, or the night blackness scary. So Papa always took the time to walk out with her. He would stay close by and whistle until she was finished. That whistling made all the difference in the world to Mama and her feeling of security returned to her in ample measure.

Perhaps the feeling of insecurity was in part due to her early childhood. Her own mother died of pneumonia when Mama was five, Barbara was eight, Conrad, the oldest, was eleven and the baby, George, was two. Grandpa Gabelein was a schoolmaster in a boys school in Bayreuth, Bavaria. He was at a loss to care for his children, so a few months later he married a spinster lady. She had apparently known the family. In fact, she had attended the funeral of his first wife. On the day of the funeral, the lady had made up her mind to become the second Mrs. Gabelein. She had started her campaign by ogling the bereaved husband and father at the service. With his need for a wife and her desire to become one, it was only a matter of a decent interval before the children had a new Mother.

However, the new Mrs. Gabelein wanted the husband, but tolerated the children as a necessary evil. There was never any feeling of affection between the new mother and the family. The children learned early to support and comfort each other. As soon as they were old enough, they were required to do the heaviest kind of physical labor. The brunt of the new Mrs. Gabelein’s malice was borne by the two girls.

Grandfather Gabelein had a comfortable home and was able to give his children certain advantages, which other people could not do. He wanted his girls to have music lessons, but opposition from the Page 30 step-mother made it impossible. However, the boys were educated in music and from her brothers Mama learned to play simple tunes. They also received a better than average education, as their Father, who must have been an excellent teacher, taught them at home. From her Father, Mama developed a thirst for knowledge that she tried to pass on to her own children.

More and more pioneers began to settle in the Reardan area. Many of them were German. The newly married Fred Wagners welcomed the newcomers, especially if they spoke the old familiar language. Papa and Uncle Charlie had written so enthusiastically to the family back in Saxony about the Washington Territory, that first one and then another made the trek out. There was Adolph, who settled on the quarter just west of Papa’s place. Then sister Mollie Frankie and her husband came to farm. Brother Gustave also came out west, but he drifted around and only occasionally came to visit. Gustave was the jolly one, and Mama and Papa always looked forward to his stay with them with a great deal of anticipation. Finally, there was Gottlied, who was in the Reardan area for several years before he left. One more sister, Minna came out to Qshkosh, so there were not too many of the Wagner clan left on the river Saale.

Mama, after two years of married life, was expecting her first baby. It had been over two months now since she had felt life within her. How she hoped for a boy. “Sons are so important to their Papas,” she thought. The baby was due in December, which was good, as Papa’s work outside was at an ebb then and he could give her some help. He’d be good help with the new one, she knew, as she had watched Papa nurse a sick animal, or with surety assist a cow or a horse with a difficult delivery.

An evening in early October, as Mama went to bed, she thought her back seemed to be bothering her more than usual.

“What could I have done today that makes my back ache so?” she confided to Papa. She moved over into the comforting circle of his arms. “Guess it isn’t too much,” she concluded, “I seem to feel better already now that I’m in bed.”

About a half an hour later there was another stabbing back pain, and then later, there was another. Mama awakened Papa, panic in her voice. “Fred, I’m afraid the baby is coming. How can it, when I still have a couple of months to go?” With speech, her fear was released and she melted into tears.

“Now, now, Lena, everything is just going to be fine. If our little fellow comes early, well and good. It may turn out to be a false alarm. Just to be sure, I’ll ride over after Grandma Garber and she’ll be here in no time at all. I’ll also get word to Rose Harder to come as soon as she can.”

After what seemed an eternity, Mama finally heard the welcome voices outside. Grandma Garber came into the bedroom and took complete command. She was an old hand at delivering babies. “The first baby always seems pretty bad, but we’ll have you through this soon” was her first statement.

The pains were increasing in regularity and intensity. What Grandma Garber observed, as she examined Mama, was that the birth would not be a normal one. In a non-commital way she quietly spoke, “Fred, come into the kitchen.” When they left the bedroom, she turned to him and in a most serious manner continued; “Lena is going to have a hard time. It’s a breech case.”

Momentarily he paused, thought over this statement, and then answered, “Do you mind if I ride over and get Doctor Coolbaugh?”

“If you feel that is what you want to do, that’s all right with me. I know how you feel about a first baby.”

Papa went into the bedroom. He knelt down by the side of the bed and cupped Mama’s face in his strong gentle hands. “Lena, Grandma Garber tells me the baby is coming buttocks first. I want to go get Doctor Coolbaugh. You know I’m depending on you to bear up until I get back. I’ll make it as fast as I can.”

Again, for the second time that night, Papa mounted his horse. His ride was much longer this time, as Edwall was eighteen miles away. The sky was full of stars. In a few moments, his eyes accustomed themselves to the night’s half-light. Swiftly and surely his horse galloped on.

It was still dark, but morning was not far away, as the two men drew rein and entered the house. In moments, Doctor Coolbaugh took over. Only the moans from Mama’s lips and the swift commands of the doctor filled the room.

At last it was all over. Doctor Coolbaugh held a little pint-sized baby in his hands. A slap or two on the buttocks, a little gasp, a whimper, thus from time immemorial the final act of birth.

“He’s all there. All that’s needed for a boy. But he is mighty little.” The Doctor hefted him in his hand. “I’d judge he weighs about two, two and a half pounds, maybe. Don’t know whether he’ll make it or not, Mr. Wagner. Keep him warm, even heat if you can manage it.”

The weary Doctor washed his hands, cleaned his forceps, put them in his bag and prepared to leave. Papa walked out with him. “Thank you so very much. My wife, Lena?” his voice trailed to a whisper, as tears filled his eyes.

“Don’t worry about her. She’ll be all right. And if the little fellow doesn’t live, there will be others.”

Meanwhile, Grandma Garber had cleaned up and swathed the new baby. When Papa returned to the kitchen, she was ready with her orders. “I want a box, a little wooden box that we can keep on the oven door. It will be a good place to keep the baby warm. We’ll keep the door open, keep a steady, low fire and that should give this young man a chance to grow. Rose is a good, dependable girl, even though she’s only sixteen, and between the two of you, you’ll make out fine.”

Rose Harder stayed about ten days. As there was only the big bed in the house, Rose slept with Mama while Papa made a pallet for himself in the loft. Thus, the first of the Wagner children slowly, but surely continued to grow.

Thereafter, babies made their appearance with regularity. By October of the following year, a baby girl, Louise was born. A year later, twin boys were born, who survived only a few days. Papa built a little casket for them, and with heavy heart Papa and Mama, with a few sympathizing neighbors, gathered on the hill above the lake for a burial service.

One more boy, Herman, was born and then in steady succession one girl after the other—Anne, Bertie, Rose, Minna. I came along seven years later, but that’s another story.

CHAPTER FIVE: Morals and Manners

Papa made us walk the straight and narrow, and there was to be no shilly-shallying either, in the process. He took the responsibility of fatherhood very seriously and was determined to see that we would grow up to be upright, honest and moral offspring of whom he could be proud. There were times when, I am sure, he must have wondered where he failed, but that didn’t stop him from trying. As a child, I was sure he preached on behavior at any drop of a hat. I thought I learned not to listen to him, but I guess I absorbed more than I realized. When you came right down to it, Papa set an example by his own actions, which was probably the best training of all.

He set a high standard of morality for himself and expected the same from others. When one of his brothers moved the fence posts from their common survey line to gain a bit more land for himself at Papa’s expense, Papa took his case to court to prove his right, and never spoke to his brother again. This action of our uncle’s, our Father would have been incapable of doing, and I think he was especially hurt because he had to acknowledge to himself that his brother had feet of clay.

On the other hand, when the county assessor made his yearly call, Papa was human enough to depreciate the worth of his livestock, his machinery and other possessions, to keep his taxes as low as possible. This was a case of bargaining, or horse trading. He enjoyed a battle of wits and was not above bragging to us later, if he thought he had been rather clever.

It must have been when I was in the fifth or sixth grade when I learned the magic words “Charge it.” I’m not sure how long this went on, but I guess several months. I’m not exactly sure how it started, but Velma Clinton and I were at the Fountain, Reardan’s only sweet shop, having a banana split. Apparently I didn’t have enough money to pay the bill, and the owner said I could charge it to my dad. I didn’t tell Papa about it, but I just sort of kept dropping in occasionally for the same delightful treat and going out saying, “Charge it to Fred Wagner.”

In Reardan, the merchants sent out statements once a year, usually about the first of September when the harvest was almost over and farmers had their pockets full of money. It was customary to carry an account from year to year without adding interest. A big cigar, a bag of candy and a handshake usually finished the final transaction.

This method of billing was my downfall. I was in constant state of ambivalence. One moment I suffered a very guilty conscience at what I knew was wrong, the next I was up in the clouds, as I savored each mouth-watering spoonful of strawberry and vanilla ice cream, chocolate sauce, pineapple sauce, banana and chopped nuts.

How was I ever going to get that bill paid without Papa knowing about it? I tried everything I could think of, to no avail. Papa, once while walking home, had found a poke containing seven hundred dollars in gold. If he could do so, couldn’t it be repeated? For weeks and weeks, as I walked the mile and a half to school and then back home again. I kept my eyes glued to the front and side of the road, hoping against hope to find enough to take care of my dilemma.

“If Papa searched around until he found the man who lost his money so he could return it to him, well, that was his business,” I mused to myself. “Of course, if I really found a lot I might just keep out enough and return the rest.”

Florence Moon, in a moment of confidence told me, “If you really want a wish to come true, then take anything made of iron that you find and put it under a flat rock. Make your wish with your eyes closed and it is sure to come true.” All the nuts, bolts or nails that came my way, I towed away under a big slab of shale I found down by the lake. I figured if one article would do the trick, a whole bunch would be better. Fervently, I wished again and again, “Please oh please, let me get that bill paid.”

Well, my wish did come true, but not in the fashion I envisioned. Papa found out. I got a dreadful scolding, but Anne sort of cushioned the blow by getting Papa to give me a little allowance.

If Papa was inclined to scold or lecture us about our behavior, Mama used the more direct method of a good swat on the behind. When Herman was about eleven, there was a time that Mama spanked him every day, whether he needed it or not, just to be on the safe side. As she became ill and lost her energy, she asked Papa to take on the job. He didn’t really think too much good came of spanking and the only time I got it was when Papa lost his temper. When he had to take on a spanking job for Mama, he’d whisper “Now yell good and loud” as he put us over his knee. He’d slip his hand off in such a way that it didn’t hurt much.

Mama wanted her girls to be gentle, ladylike, neat and as beautiful as possible. We all learned to love pretty clothes, because Mama loved them so much. She had a number of beauty aids, as for instance, the buttermilk massage on face, arms and hands every churning day. The skin did feel soft, but we must have smelled like a dairy. There was a weekly washing of long hair, scalp inspection and danderine application and endless brushing. One cupboard was filled with homemade cold cream, glycerine and rose water hand cream and other recipes we found in the Delineator magazine.

Lou was Mama’s best pupil when it came to neatness. When she became chief housekeeper, she waged a never-ending war on the dust, the mud or the dirt. Windows were washed and bonami polished weekly, the woodwork wiped down with a damp cloth, while lamp chimneys had to be washed and polished with newspaper any time they showed a smudge of smoke. Yearly, the Brussels carpet of red cabbage roses and green leaf design on a beige background, was taken up from the parlor floor, put on the clothes line and beaten with a flail until no more dust would come out.

In 1908, Lou went into Spokane for ten weeks to attend dressmaking school. She learned to draft patterns, design, cut and sew the intricate fashions of the day. Several years later she returned to Spokane for a course in millinery. Her hats were as beautifully made and styled as her clothes, as she seemed to have a natural aptitude for this type of creative work. The sewing machine was kept under the big window in the dining room and almost daily, Lou would find some time to do a bit of sewing for one or the other in the family.

One letter of mine, still extant, gives this bit of information: “I have a new coat out of Resla’s old one.” I remember that coat, a brown woolen fabric with a big plush collar and a muff to match. The material for the trim was apparently new, the basic fabric re-utilized. I loved Page 36 that coat and almost wore down the pile of the plush by stroking it. Papa often sat in the rocking chair in the dining room, watching as I stood on the table while Lou adjusted hem lines. He always had some comment to make. Lou would say, “Now Papa, that is the fashion this year,” if he questioned a particular style. He was usually willing to be convinced, although often he had to make up a joke about it.

The weekly washing, especially in the summer time, was an all day job. The long white stockings I wore were usually grass stained and had to be smeared with butter before they could be put in with the white things to be boiled. Sheets, towels, petticoats, corset covers, all were boiled on the kitchen stove for twenty minutes before they were put in the washer, which was agitated by hand. The laundry soap was made at home from the animal fats and lye. Lou usually made the soap out-of-doors in the fall. The clothes line was filled to bulging and often Lou would take time out to admire the whiteness of the clothes.

Tuesday was the day for ironing. From after breakfast until the noonday meal, there were at least two ironing boards in use with half a dozen sadd irons heating on the stove. It took time to iron the cotton, voile or dimity dresses, all flounced, gathered or ruffled in some degree.